Revista Música Hodie, Goiânia - V.14, 269p., n.2, 2014

Cláudia Maria Gomes de Sousa (Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal)

Henry Johannes Greten (Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas - Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal)

Jorge Machado (Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas - Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal)

Daniela Coimbra - Coordenadora do Projeto (Escola Superior de Música e das Artes do Espetáculo do Porto - ESMAE/IPP - Instituto de Investigação em Artes, Design e Sociedade da Universidade do Porto)

A prevalência de lesões músculo esqueléticas relacionadas com o trabalho (LMERT) entre músicos de orquestras

profissionais

Background

The prevalence of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMSD) among mu- sicians is well documented in literature (Ostwall et al., 1994). Lockwood (1989) reported that almost 50% of musicians experience PRMSD to a level that could threaten or end their careers. According to Zaza (1998) the percentage of affected musicians ranged from 39% to 87% in adult musicians and from 34% to 62% in secondary school music students. More recent data states that 50% to 76% of musicians are affected by PRMSD (Heinan, 2008). An Australian study that involved 485 orchestra musicians referred to a 42% prevalence of PRMSD (Fry, 1996) while 86% of elite professional musicians of British symphonic orches-

Revista Música Hodie, Goiânia - V.14, 269p., n.2, 2014 Recebido em: 03/08/2014 - Aprovado em: 20/09/2014

tra claimed to have suffered some type of musculoskeletal pain during the last year (Leaver, Harris, Palmer, 2011).

However, in spite of the historical importance of such statistics it is clear that the problem of PRMSD among musicians is far from being solved, since the numbers have re- mained almost the same over several years. Common solutions used to treat musculoskel- etal complaints include rehabilitation programs and drugs such as paracetamol, a very well-known pain killer (Schnitzer, 2006). In fact, 49% of orchestra musicians mention the use of paracetamol to control their pain and 64% had been examined or treated by a health care professional, such as a physiotherapist (Paarup, 2011). However, according to Curatolo and Bogduk (2000), many drugs are ineffective while others reduce pain only modestly and brieflyand have only a minimal effect on musicians’ quality of life. Other strategies include rehabilitation programs, and the recommendation to stop playing, with approximately one third of the affected musicians having to stop playing for a period of time (Heming, 2004).

PRMSD may bring emotional, physical, financial, occupational and social conse- quences to a musician’s life (Zaza, Charles and Muszynski, 1998). The fear of losing their work might be responsible for the dangerous attitude of ignoring pain, the symptoms re- quiring treatment or the necessary rest (Suskin et al. 2005; Llobet, 2004; Shafer-Crane 2006). The consequence of this behaviour may be the development of acute to chronic con- ditions. Indeed, musculoskeletal disorders often become chronic and painful causing de- creased quality of life (Zaza, 1998; Lockwood, 1989). Data shows that 73% of orchestra mu- sicians mention the need to change their way of playing, 55% reported feeling difficulty in daily activities at home, and 49% reported having difficulty in sleeping (Paarup et al., 2011). PRMSD may also have a negative impact on the quality of a musician’s performance and Ackermann et al. (2012) or Zaza et al (1998) suggest that PRMSD adversely affect a mu- sician’s ability to play to their optimum level.

According to the Portuguese Health Ministry, an occupational disease is a condi- tion directly caused by working conditions that can lead to incapacity or death during per- formance of the occupation (Decreto Regulamentar Nº 76/2013). Unfortunately, perhaps because of the fact that performing arts are so much a part of everyday life, they are not re- garded as a perceived occupation and job (Lederman, 2003). However, like many other oc- cupational diseases, PRMSD have multifactorial causes and several risk factors that could contribute to their onset.

As common occupational diseases, factors such as awkward static or dynamic pos- tures, repetitive movements, unhealthy habits, the lack of ergonomic precautions and pre- ventive wellness behaviour, age, gender or stressful environments could influence their onset (Costa, Vieira, 2010; Paarup et al, 2011). Additionally, individual issues specifically related to musicians’ activity such as technique, number of years of experience, type of rep- ertoire, previous trauma, or the individual adaptation to the instrument itself, could influ- ence the appearance of PRMSD (Frank and Mühlen, 2007; Fragelli, et al, 2008; Wu, 2007; Hansen & Reed, 2006;Nyman, 2007). As previously mentioned, it is also known that organi- zational management and working environment could influence the prevalence of PRMSD. The extremely competitive environment, the self-imposed pressures, the average of playing hours, inadequate material resources or warm-up before playing could highly influence the development of PRMSD (Cohen and Ratzon, 2011).

Zander et al (2002) identified 3 main groups of risk factors that can preclude the de- velopment of PRMSD: environmental aspects, physical demands and activities, and person- al characteristics. Environmental aspects include temperature, confined spaces, space lay-

out, equipment, equipment layout or configuration, surfaces (floor) and lighting. Physical demands include aspects such as long-duration activities with inadequate rest and person- al characteristics include e.g. psychological stress, age and gender.

If some of those causes and risk factors such as the musicians’ individual char- acteristics could not be changed, variables related to environmental aspects and working conditions within the orchestra framework, such as adequate material resources, could be ameliorated. Recent studies alert that providing adequate working conditions could reduce the appearance of PRMSD (Shafer-Crane, 2006; Zander et al, 2002). For instance, depend- ing on the problem, ergonomic instrument modifications may influence the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain. To avoid diseases related to incorrect body posture, which can influ- ence the appearance of muscle or spinal injuries, it is necessary to keep the body in an er- gonomically recommended posture during a musical performance. To control this problem, the chair should be adapted to the musician’s individual characteristics. It must be support- ive in order to maintain a proper posture that allows a view of the conductor (Heinan, 2008; Suskin et al, 2005).

Light and temperature conditions in the rehearsal and concert room can also in- fluence the onset of PRMSD. Poor light conditions could cause eyestrain and cool temper- atures slow nerve conduction, making the finger response harder and diminishing finger sensitivity (Hansen and Reed, 2006; Norris, 2011).

The possibility of taking breaks during practice is also very important. Taking short breaks during long practice could contribute to reducing the appearance of musculo- skeletal pain (Zaza and Fareweel, 1997, Zander et al). In addition to this, Suskin et al (2005) suggest that warming-up and breathing exercises before performance, and strengthening and stretching exercises are considered to be good health habits to prevent PRMSC among musicians. According to the authors, regular health examination by a doctor must also be included within those preventive strategies and therefore it is very important that the or- chestra management provides musicians with a medical examination to diagnose health problems like hearing alterations, psychological stress or physical complaints, among oth- ers conditions.

One other aspect to consider is the fact that musicians are subjected to noise ex- posure that could threaten their hearing acuity and is responsible for hearing impairment. Therefore, the orchestra should provide individual solutions to hearing protection in or- der to prevent future damage (Royster, Royster, and Killion, 1991; Hansen and Reed, 2006; Behar, Wong, and Kunov, 2006; Russo et al, 2013)

As previously stated, the fear of losing work is one of the main facts responsible for musicians neglecting their musculoskeletal problems. Consequently, a stable work contract could alter this behaviour and have a positive influence on the chronicity of PRMSD. Maybe if musicians know that their job is secure, they treat their injury at an earlier stage.

According to Allemendiger (1996), managers and artistic directors are in the chal- lenging position of providing stability to the orchestra. Creating opportunities, promoting the professional development of musicians, controlling the fairness and efficacy of the re- cruitment/selection process, dealing with the conception of authority and promoting ade- quate financial and material resources are some of the variables that could influence the working stability of musicians.

By analysing all these preventive strategies one could define adequate working conditions as:

The presence of ergonomic chairs exclusively made to respect the individual characteristics of the musician, stable light and temperature conditions and a fixed rehearsal room;

The possibility of taking adequate breaks during rehearsal;

The possibility of using hearing protection;

The possibility of having regular health examinations to prevent hearing im- pairment and the appearance of PRMSD;

A stable work contract.

Method

The aim of this research was to ascertain whether there is an association between the defined adequate working conditions and the prevalence and severity of playing-related musculoskeletal complaints. The inclusion criteria to consider that the orchestra has ade- quate working conditions were as below:

The presence of ergonomic chairs exclusively made to respect the individual characteristics of the musician,

Fixed rehearsal room,

Stable light and temperature conditions in the rehearsal room

Adequate breaks during rehearsal

Possibility of using hearing protectors

Regular health examinations

Stable work contract

Three professional orchestras from Portugal were invited to take part in this re- search, totalling 162 professional orchestra musicians. To form part of the study the musi- cian had to comply with the following inclusion criteria:

Musculoskeletal pain present at the time of the interview and stable for at least seven days

Diagnosis of PRMSD by a physiotherapist

In an individual semi-structured interview acute playing-related musculoskeletal self-reported complaints (PRMSC) and their intensity (measured by Verbal Numeric Scale- VNS) were registered. The data was collected between September of 2012 and June of 2013 after ethical approval and the informed consent of all participants, in accordance with the Helsinki declaration.

The numeric verbal scale (NVS) for pain intensity is a valid instrument to assess changes in pain intensity and it is one of the most frequently used pain scales (Holdgate et al, 2003). The person estimates their pain on a scale of 0 to 10 (Sousa and Silva, 2005). 0 represents no pain, from 1 to 3 represents mild pain, from 4 to 6 represents moderate pain and from 7 to 10 represents severe pain.

VNS values were analysed using SPSS (version 21.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Mann-Whitney test was performed to analyse the difference of VNS values be- tween groups (Fortin, 1999).

Results

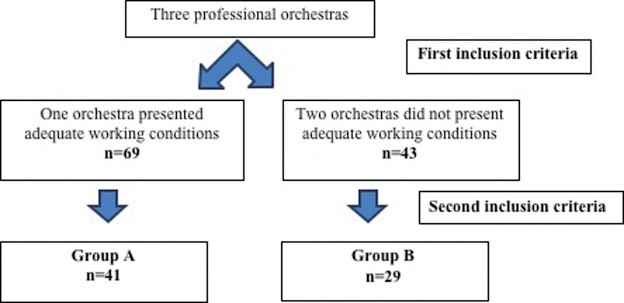

1st inclusion criteria

One out of the three professional orchestras complied with the inclusion criteria and 69 out of 89 (77.5%) musicians agreed to participate into the study- Group A

Two out of three professional orchestras did not comply with the inclusion criteria and of those 43 out of 73 (68.9%) musicians participated in this research – Group B

2nd inclusion criteria

41 out of 69 (59.4%) musicians of group A complied with the inclusion criteria and 29 out of 43 (67.4%) musicians of the group B complied with the inclusion criteria.

The recruitment procedure is represented in the following flow chart

Figure 1: Recruitment flow chart

The following table contains the sample characteristics.

Table 1: Sample characteristics

Age | Gender | |

Group A (n=41) | 41.7 (SD=8.9) | 14 women (34%) |

Group B (n=29) | 31.8 (SD=7) | 11 women (38%) |

As shown in table 2, group B has a higher percentage of self-reported PRMSC (67.4%) than group A (59.4%). However, the number of complaints per affected musician is higher in group A (1.9 against 1.6).

Table 2: prevalence of self-reported PRMSC

Interviewed | Self-reporting PRMSC | % of affected musicians | Number of reported complaints | Complaints/ Musician | Complaints/ affected musician | |

Group A | n= 69 | n=41 | 59.4% | 79 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

Group B | n=43 | n=29 | 67.4% | 47 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

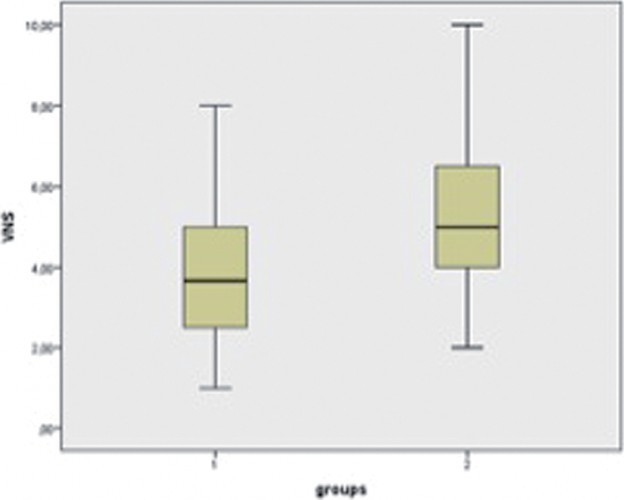

Pain intensity was measured by verbal numerical scale (VNS) from 0 to 10. Table 3 and figure 2 show the VNS values.

Table 3: Pain intensity

Group A | Group B | |

VNS | 4.0 (SD=1.9) | 5.1 (SD=1.9) |

Figure 2: Distribution of VNS values

Results show that comparing VNS values through a Mann-Witney test, VNS values are statically significant (p value= 0.021).

Discussion

Results show a higher percentage of PRMSC among group B. The difference be- tween groups is 11%. This value suggests that working conditions may influence the preva- lence of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders. Although the percentage of affected mu- sicians is higher in group B, the number of self-reported complaints per affected musician is higher in group A. Despite the fact that the difference between groups is almost nil (0.3), it is important to consider that those data came from interviews and the complaints were self-reported by the musicians. According to Suskin et al. (2005), Shafer-Crane (2006) and Llobet (2004) the recommendation to stop playing and the fear of losing their work could be responsible for a dangerous tendency to ignore pain and symptoms requiring treatment or rest. It is also important to bear in mind that group A has more stable working contracts than group B. In this way, we can speculate that perhaps the musicians of group B tend to ignore some of their complaints because they fear losing their jobs.

As far as pain intensity measured by VNS is concerned, results clearly show a sta- tistical difference between groups (pvalue=0.021). Group B (VNS=5.1) states more intense musculoskeletal pain than group A (VNS=4.0). Those results also tally with the hypothesis that working conditions may influence the severity of PRMSD. Nevertheless, those values are concerning because musicians are working with moderate pain.

Literature states that PRMSD could be explained by several causes and several risk factors could preclude their appearance. Individual musicians’ characteristics like age and gender have a strong influence on the prevalence of PRMSD. Women are more af- fected than men and increased age is also a risk factor to their development (Paarup et al, 2011, Lobet, 2004, Russo et al, 2013). As regards gender, our sample is equivalent, and thus we can affirm that the difference between pain intensity could not be explained by this variable.

In our sample the difference between ages in group A and B is 10 years. A study performed with 1613 musicians of different ages and professional levels demonstrated that 90% of the musicians aged between 30 and 40 were affected by physical problems, com- pared with 55% in adults aged from 20 to 30 (Llobet, 2004). According to this informa- tion, it could be expected that older musicians present a higher prevalence and severity of PRMSC than younger musicians. In terms of the age variable it could be expected that group A presented more PRMSD than group B. This was not the case and the highest per- centage of PRMSD in group B may well be explained by the influence of adequate work- ing conditions preventing PRMSD, since musicians in Group B are younger but work under poorer working conditions.

Taking another perspective, it is known that the lack of efficacy of individual tech- nique could also contribute to musculoskeletal pain. Although we are aware of the difficul- ty of defining a good individual technique, we can speculate that perhaps older musicians present a technique which is more adequate to the function they perform than younger mu- sicians and therefore this variable could also have influenced our results.

Yet another perspective is presented by Warrington (2002), according to whom PRMSD must be analysed by three different pathological groups: “trauma” “degenerative” and “non-specific pain”. The author states that there are no differences between ages in the prevalence of PRMSD caused by trauma. Degenerative conditions are most common over- the age of 40, but “non-specific arm pain” is much higher in musicians under 25. Thus, al- though age could help to explain our results, there are several variables which are impos- sible to control.

Conclusion

According to our data, the prevalence and intensity of playing-related musculo- skeletal disorders is associated with less adequate working conditions, suggesting their im- portant role in professional musicians’ health and well-being. In fact, it is documented that PRMSD have multifactorial causes and risk factors, and that adequate working conditions proved to be an important variable to promote good quality of life.

Although adequate working conditions are important to promote a good working environment, other variables should also be considered. As Allmendiger (1996) suggested, the orchestra management board is in the challenging position of providing the orchestra with stability, creating opportunities, promoting the professional development of the or- chestra musicians, and promoting adequate financial and material resources. Nevertheless, adequate working conditions could be expensive. Providing stable contracts, the aforemen- tioned ergonomic chairs, or adequate rehearsal rooms costs money. But it is our belief that the investment may prove worthwhile when the expected number of sick leaves decreases. However, the monetary factor is not the most important at play. Institutions and the indi- viduals that work in them have a lot to gain if a healthy orchestra is to be promoted and it is everyone’s moral and ethical duty to promote the healthiest possible working environment. Although it is known that PRMSD have multifactorial causes, it is difficult to iso-

late and to study only one of those causes, risk factor or variables. Our results do not allow the establishment of a direct cause-effect relationship between adequate working condi- tions and the prevalence and intensity of PRMSD. We are aware that variables like gen- der, age, repertoire or individual technique could not be changed or controlled by us and that they could have influenced our results. This fact represents the main limitation of our study and further studies are needed to ameliorate our conclusions.

Nevertheless, our results tally with the hypothesis that adequate working condi- tions may influence the prevalence and the severity of PRMSD in professional orchestra musicians. It is possible to change this variable. Providing adequate material and stable working conditions is an ethical duty of both employers and their co-workers. The orches- tra management has also the ethical duty of preserving quality of life, promoting health and avoiding illnesses among musicians and of promoting more responsible behaviour on the musician’s part. With this research we hope to have raised awareness about the importance of adequate working conditions, especially when research at a national level in Portuguese orchestras is so scarce.

References

ACKERMANN B, DRISCOLL T, KENNY D. 2012. Musculoskeletal pain and injury in pro- fessional orchestra musicians in Australia.Medical Problems of Performing Artists, v.27, n.4, p. 181-187, 2012. Available from: http://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/journalviewer. aspx?issue=1198&article=1962. Cited in: 2014 January 31.

ALLMENDINGER J, HACKMAN R, LEHMAN E. Life and work in symphony orchestras.

Musical Quarterly, London, v.40, n.20, p 194-219, 1996.

BEHAR A, WONG W, KUNOVH. Risk of hearing loss in orchestra musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. n.4, p. 64-168, 2006 Available from: http://individual.utoronto.ca/willy/ review.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 21.

COHEN K, RATZON N.Correlation between risk factors and musculos keletal disorders among classical musicians. Occupational Medicine. n.61, p. 90-95, 2011. Available from: http://occmed. oxfordjournals.org/content/61/2/90.full. Cited in: 2014 March 21.

COSTA B, VIEIRA E. Risk Factors for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review of Recent Longitudinal Studies. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. n.53, p. 285-323. 2010. Available from: http://www.nersat.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Risk_ Factors_for_Work_Related_Musculoskeletal_Disorders_A_Systematic_Review_of_Recent_ Longitudinal_Studies1.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 30.

CURATOLO M, BOGDUK N. Pharmacologic Pain Treatment of Musculoskeletal Disorders: Current Perspectives and Future Prospects. Clinical Journal of Pain. n.17, p. 25-32, 2001. Available from: http://journals.lww.com/clinicalpain/Fulltext/2001/03000/Pharmacologic_ Pain_Treatment_of_Musculoskeletal.5.aspx. Cited in: 2014 January 31.

Decreto Regulamentar n.º 76/2007. Lisboa: Diário da República. 2013. Available from: http:// www.min-saude.pt/NR/+rdonlyres/AF267FFC-1E51-41DC-8736-D52019BCAB6F/0/0449904543. pdf. Cited in: 2014 January 2.

FORTIN MF. O processo de investigação: da concepção à realização. Loures: Lusociência,1999, p 388.

FRAGELLI T, CARVALHO G, PINHO D. Musician’s injuries: whenpainovercomesart. Rev Neurosciences. n.16, v.4, p. 303-309.2008. Available from: http://twingo.ucb.br:8080/jspui/bit- stream/10869/293/1/Les%C3%B5es_m%C3%BAsicos.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 30.

FRANK A, MÜHLEN C. Playing-Related Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Musicians: Prevalence and Risk Factors. RevistaBrasileita de Reumatologia. n.47, v.3, p. 188-196. 2007. Availablefrom: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0482-50042007000300008&script=sci_ arttext&tlng=es. Cited in: 2014 March 30.

FRY H. 1986. Incidence of overuse syndrome in the symphony orchestra. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. n.1, p. 51-5, 1986. Available from: https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa/jour- nalviewer.aspx?issue=1152&article=1514&action=1. Cited in: 2014 January 31.

HANSEN P, REED. Common Musculoskeletal Problems in the Performing Artists. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinic of North America. n.17, p. 789-801, 2006. Available from: http://www.med.nyu.edu/pmr/residency/resources/PMR%20clinics%20NA/PMR%20clin- ics%20NA_performing%20arts%20medicine/MSK%20problems%20in%20performing%20art- ists.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 30.

HEINAN M. A review of the unique injuries sustained by musicians. JAAPA. n.21, v.4, p. 45-51. 2008. Available from: http://media.haymarketmedia.com/documents/2/musician0408_1280.pdf. Cited in: 2014 February 15.

HEMING M. Occupational injuries suffered by classical musicians through overuse. Clinical Chiropractice. n.7, v.2, p. 55-66, 2004. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S1479235404000185. Cited in: 2014 February 15.

HOLDGATE A et al. Comparison of a verbal numeric rating scale with the visual analogue scale for the measurement of acute pain. Emergency Medicine. n.15, v.5-6, p. 441-446, 2003.

LEAVER R, HARRIS E, PALMER T. Musculoskeletal pain in elite professional musicians from British symphony orchestras. Occupational Medicine. n.61, p. 549-555, 2011. Available from: http://occmed.oxfordjournals.org/content/61/8/549.full. Cited in: 2014 February 10.

LEDERMAN R. Neuromuscular and musculoskeletal problems in instrumental musicians. Muscle nerve. n.27, v.5, p. 549-561, 2003. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/resneuro/ emg/resources/Monograph43InstrumentalMusicians.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 15.

LLOBET R. Musicians health problems and in their relation to musical education.Barcelona and Tenerife: XXVI Conference of the International Society for Music Education & CEPROM Meeting; 2004. Available from:http://institutart.com/index./ca/divulgacio/item/musicians-health-prob-

lems-and-in-their-relation-to-musical-education. Cited in: 2014 February 10.

LOCKWOOD M. Medical Problems of Musicians.New England Journal of Medicine. n.320, p. 221-7, 1989. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM198901263200405.

Cited in 2014 February 15.

NORRIS, R. The musicians`s survival manual – A guide to preventing and treating injuries in in- strumentalists. 5th Edition. Northampton: ICSOM. 2011. Available from http://musicianssurvival- manual.com/Download_Book_files/Final%20master%20MSM.pdf. Cited in: 2014 February 20.

NYMAN T, et al. Work postures and neck–shoulder pain among orchestra musicians. American Journal of Industrial Medicine.n.50, v.5, p. 370-376, 2007. Available from: http://onlinelibrary. wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajim.20454/abstract.Cited in: 2014 January 21.

OSTWALD et al. Performing arts medicine. West Journal of Medicine; n.160, p. 48- 52, 1994. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1022254/pdf/

westjmed00065-0050.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 21.

PAARUP H,et al. Prevalence and consequences of musculoskeletal symptoms in symphony orchestra musicians vary by gender: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. n.12, p. 223. 2011. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/223/. Cited in: 2014 January 31.

ROBINSON D, ZANDER J, RESEARCH B. Preventing Musculoskeletal Injury (MSI) for Musicians and Dancers: A Resource Guide. Vancouver, Canada: SHAPE (Safety and Health in Arts Production and Entertainment). 2002. Available in http://www.actsafe.ca/wp-content/uploads/ resources/pdf/msi.pdf. Cited in: 2014 January 31.

ROYSTER J, ROYSTER L, KILLION C. Sound exposures and hearing thresholds of symphony orchestra musicians. Journal of Acoustic Society America. n.89, v.6, p. 2793-2803, 1991. http:// www.etymotic.com/publications/erl-0022-1991.pdf. Cited in: 2014 March 25.

RUSSO F, et al. Noise exposure and hearing loss in classical orchestra musicians. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomy. n.43, p. 474-478, 2013. Available from: researchgate.net. Cited in 2014: March 14.

SCHNITZER, T. Update on guidelines for the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clinical rheumatology. n.25, v.1, p. 22-29,2006. Available from: http://link.springer.com/arti- cle/10.1007/s10067-006-0203-8.Cited in: 2014 February 15.

SHAFER-CRANE G. Repetitive stress and strain injuries: preventive exercises for the musi- cian. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinic of North America. n.17, v. 4, p. 827-842, 2006. Available from: http://www.med.nyu.edu/pmr/residency/resources/PMR%20clinics%20NA/ PMR%20clinics%20NA_performing%20arts%20medicine/Repetitive%20Stress%20and%20 Strain%20Injuries%20Preventive%20Exercises%20for%20the%20Musician.pdf. Cited in 2014 January 21].

SOUSA F, SILVA J. 2005. The metric of pain: theoretical and methodological issues. Revista dador. Lisboa. n.6, v.1, p. 469-513, 2005.

SUSKIN E et al.Health Problems in Musicians – A Review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat? n.13, v.4, p. 247-251. 2005.

WARRINGTON J, WINSPUR I, STEINWEDE D. 2002. Upper-extremity problems in musicians related to age. Med Probl Perform Art 17(3): 131-134.

WU S. Occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders in musicians: a systematic re- view. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. n.22, v.2, p. 73,2007. Available from: https://www. sciandmed.com/mppa/journalviewer.aspx?issue=1083&article=935. Cited in: 2014 January 14.

ZAZA C, CHARLES C, MUSZYNSKI A. The meaning of playing-related musculoskeletal dis- orders to classical musicians.Society Science Medicine. n.47, v.12, p. 2013-2023, 1998. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953698003074. Cited in: 2014 March 30.

ZAZA C, FAREWELL V. Musicians’ playing-related musculoskeletal disorders: an examination of risk factors. American Journalof Industrial Medicine. n.32, v.3, p. 292-300, 1997. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199709)32:3%3C292::AID- AJIM16%3E3.0.CO;2-Q/abstract. Cited in: 2014 April 16.

ZAZA C. Playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians: a systematic review of in- cidence and prevalence. Canadian Medical AssociationJournal. n.158, v.8, p. 1019-1025, 1998. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1229223/pdf/cmaj_158_8_1019. pdf. Cited in: 2014 January 2.

![]()

![]()